CHICAGO – In anticipation of the scariest week of the year, HollywoodChicago.com launches its 2024 Movie Gifts series, which will suggest DVDs and collections for holiday giving.

Interview: Alan K. Rode Brings ‘Noir City’ to Chicago’s Music Box Theatre

CHICAGO – Along with sixteen restored 35mm prints of overlooked cinematic gems, the Music Box Theatre’s third installment of “Noir City: Chicago” brings two renowned film historians to the Windy City: Alan K. Rode and Foster Hirsch. Both men serve on the board of directors of the Film Noir Foundation, a non-profit corporation aiming to restore rare noir classics for future generations.

In addition to serving as the co-programmer and co-host of the annual Noir City Hollywood film festival, Rode is also the charter director and treasurer of the Film Noir Foundation as well as the producer, programmer and host of the Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival in Palm Springs, California. He garnered acclaim for his book, “Charles McGraw: Biography of a Film Noir Tough Guy,” which followed the titular prolific actor through the rise and fall of the studio system. His latest book, “Michael Curtiz: A Man for All Movies,” is set for a 2013 release from the University Press of Kentucky. HollywoodChicago spoke with Rode about some of his favorite selections at this year’s festival, the meticulous process of film preservation, and his thoughts concerning one of film noir’s most overlooked and vital figures, producer Mark Hellinger.

HollywoodChicago.com: How did you first meet Eddie Muller, your partner-in-crime at the Film Noir Foundation?

Alan K. Rode: It all started back in 1999 when the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles bought The Egyptian Theatre from the city of Hollywood for a dollar. They refurbished the theatre because it had fallen into a state of disrepair over the years, and then they invited Eddie Muller, who had published a book on film noir in 1999 [“Dark City”], to a film festival. I came to the festival that year, met Eddie and as Humphrey Bogart said in “Casablanca,” “It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.” We have Noir City festivals in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle and Chicago. The Music Box talked to my fellow director, friend and colleague, Foster Hirsch, three years ago and we brought Noir City there. There’s another Noir City in Washington D.C., so we’re now covering the country in darkness.

Film noir expert Alan K. Rode will co-host Noir City: Chicago 3 at the Music Box.

Photo credit: Alan K. Rode

HollywoodChicago.com: Why is film preservation more vital than ever?

Rode: This country has historically treated its films with something less than respect. At one point in the 1950s, old silent films from one studio were being thrown into the ocean. We’ve always treated films differently here than in places like France, but I think there’s even more of a sense of urgency now because the whole industry is changing. We’ve seen this rapid change from VHS to DVD to digital and who knows what’s next. So a lot of rights holders and other people are really unclear as to what the future is going to be. One thing that is clear is that film is going away. If you want to preserve a film or strike a new print, that requires a number of things. Number one, you have to have all of the elements, including the negative. The rights holder has to be part and parcel of agreeing to this and going through the legal and financial hurdles.

Once you get that, then you have to apply the funds, and that’s usually where the Film Noir Foundation comes in with the money from our festivals, our products and our membership in this newsletter we call the “Noir City Sentinel.” In three years, it has morphed into a quarterly, almost hundred-page, fully illustrated magazine with some unbelievable contributions. We annually turn those into books and sell them on Amazon and our festivals. Our latest “Noir City Sentinel 3” will be on sale at the Music Box during this festival. We take that money and apply it to restoring the films. Now you have to have someone do the physical work of restoration. We’ve had a very fruitful partnership with the UCLA Film & Television Archive, which is one of the most prestigious and luminous film archives in the whole wide sweet world. However, the pipeline for doing this work as far as lab work has really narrowed. So if there are a number of different projects in the pipeline, we have to get in line with everybody else. Film preservation isn’t achieved simply because a couple people get in a room and say, “Gee, wouldn’t it be neat to get a new print of ‘The High Wall’?” [laughs] You have to work with a lot of different people, and you have to be very patient, very diplomatic and very persistent.

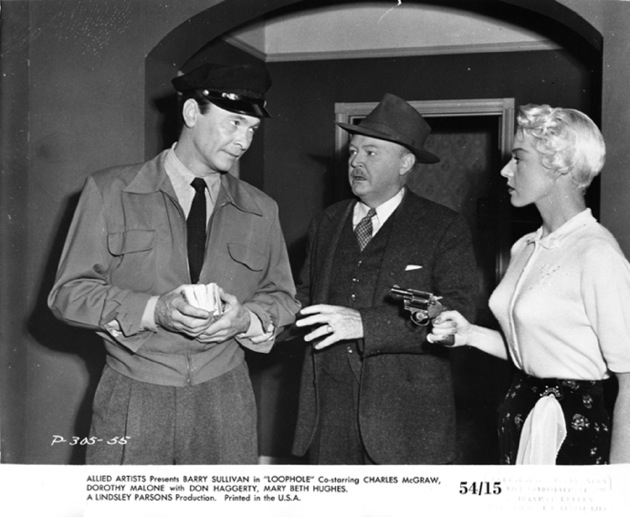

A classic example of this occurred with the picture that we’re going to screen on August 13, called “Loophole,” which was made in 1954 by Allied Artists. When I wrote my book on Charles McGraw, “Loophole” was the missing link because it featured one of the seminal McGraw roles, and was a picture from the film noir canon that had just disappeared. There were grainy DVDs that looked like they had been filmed through a piece of linoleum file. We found out Warner Brothers owned the rights to Allied Artists, and through more than a few years of patiently working with them, they did locate some elements and we were able to negotiate an arrangement where we would fund the striking of a print, and they would retain all their rights and the print would be put on deposit at the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Then we discovered that there was a reel missing and another reel dubbed in Italian. Then finally, last year, we were able to get a viable 35mm print struck but this was something that took a great deal of patience and time.

It’s important to understand that process because films are disappearing like dinosaurs. There has to be a financial advantage for the rights holders to agree to someone saying, “I don’t want you to pay attention to your current films. I want you to find some 1954 movie with Barry Sullivan in it and store it.” It has to have some meaning to them beyond “we like these films too.” So it’s a very multi-faceted type of situation, and with everything going digital now, restoring film in itself is a challenging endeavor. It’s worth doing because in addition to these films being entertaining, well written and vastly interesting, film noir really shows a time in our history when America basically grew up and went from adolescence to adulthood. I always call it post-WWII noir realism. In today’s world, it seems like the public memory is about the equivalent of what a fruit fly remembers. I think these films are important because they allow us to take a look at who we were as a culture, and how we’ve progressed or in some cases how we regressed.

Harold D. Schuster’s 1954 noir Loophole screens August 13 at the Music Box.

Photo credit: Warner Bros.

HollywoodChicago.com: Why did you choose Charles McGraw as the subject of your book on ’40s-’50s era Hollywood?

Rode: I think his career straddled the whole [era]. He was part of the Group Theater and he came to Hollywood around the same time as people like Lee Cobb, Karl Malden and John Garfield. He was of the Odets generation, when Clifford Odets had five or six plays running on Broadway at the same time. He got to Hollywood in 1942 and worked until he died in 1980. He came in during the classic studio system and then worked through the break up of the studio system, the [emergence of] television, and up until the point when the Paramount mountain logo was owned by an oil company in the 70s. I would say that McGraw chose me rather than I chose him because the circumstances of getting to know his widow and his daughter were completely serendipitous. As I formed these relationships and heard these stories about him, it occurred to me that I have to write a book about this guy and his life and times.

HollywoodChicago.com: Was there an effort made to emulate the style of noir in your writing?

Rode: No, that was just me. I guess I’m brainwashed with noir. My writing style goes to brevity. I think one reviewer said it was like a “rat-a-tat of a machine gun,” but that was just how I wrote the book. It was not a conscious choice.

HollywoodChicago.com: One key overlooked figure is Mark Hellinger, who produced this festival’s closing night selection. What are your thoughts on his contributions to noir?

Rode: Hellinger is a very interesting guy and I agree with you that his contributions to noir are often overlooked. He really was one of the pillars of the twentieth century and the new entertainment. He wrote a column about the whole Roaring Twenties of speakeasies, prohibition, Babe Ruth and New York, which was the center of the universe. At its height, his column was being read by 15 or 20 million Americans every day, and now I don’t think anyone would know who he was. Like most people who were successful in that type of endeavor, he came to Hollywood during the 1930s. It did not work out at all, but he came back and ended up at Warner Bros., and he understudied with the producer of the B-unit, Bryan Foy, one of the seven little Foys of vaudeville fame. [Hellinger] learned the craft of writing and making movies as a producer and he did some great stuff at Warner Bros. like “Manpower” and “High Sierra. He was a legendary character—black jacket, white tie, married to Gladys Glad, who was one of Ziegfeld’s loveliest showgirls. But he was not a biddable man, and certainly not someone who could work with taskmasters like Jack L. Warner or Hal Wallis for an indefinite period of time. He went to WWII with a congenital heart condition, and he was in such bad shape that he was even at risk to get the vaccination to go overseas. But he managed to wrangle his way overseas as a correspondent and came back, finished up at Warner Bros. and struck out on his own.

His big gamble was the 1946 movie, “The Killers,” one of the all-time classic film noir movies. If I had to pick one film that typifies the postwar realism of noir, “The Killers” with McGraw and Conrad entering the diner—that movie would not have been made before WWII. Hellinger hocked himself to Bank of America and came in big time. From there came a film we’re [using] to close out the Chicago festival: “Brute Force,” which may be the grimmest movie ever made during the 1940s. It’s the ultimate prison breakout movie, and there’s a lot of stuff written about how it’s an analogy for Nazism. What Hellinger really wanted to do was make a realistic prison movie and he wanted to be successful and make money. When I corresponded with the late [“Brute Force” director] Jules Dassin, he said that Hellinger forced him to put in sequences with the “women on the outside” [which the prisoners recall in flashback]. Dassin said, “I see it now and it’s so ridiculous I don’t forgive myself.” But Hellinger was also being a producer and looking at the box office. He went on to make “The Naked City,” which was the first movie filmed on location in New York City [since the silent era]. Then Hellinger had this massive heart attack when they were filming that final sequence of the character Willie Garzah running over the Williamsburg bridge, and he ended up dying in December of 1947. He had a bad heart, smoked an endless chain of cigarettes and drank about a bottle of Hennessy brandy every night. He died very young, but was certainly a legendary figure in American film noir.

Anatole Litvak’s 1948 noir Sorry, Wrong Number screens August 18 at the Music Box.

Photo credit: Paramount

HollywoodChicago.com: Some film historians have speculated that the fascist depiction of Hume Cronyn’s sinister prison guard in “Brute Force” reflected Hellinger’s view of Warner and Wallis.

Rode: I don’t think so. I think that Dassin might’ve put some of that in as an analogy for fascism and Nazism. In fact, I think Eddie Muller talked to Hume Cronyn not long before he passed away and said to him something along the lines of, “You were such an evil son of a b—h in that movie,” and he said, “I owe it all to Jules Dassin.” I’ve gone through the production files and Hellinger’s papers. He was trying to make a realistic movie, and his battles were really with Joe Breen, who was the head of the motion picture code authority.

He and Breen had a lot of emotional correspondence back and forth because Breen objected to what he called “the gruesomeness and violence and cruelty” in that movie. There were a lot of things taken out. The code prevented any mention of drugs or narcotics, and there were scenes in which characters talked about smoking marijuana and dealing drugs in prison. There was also a fight scene [that got cut] where Cronyn kicks somebody in the face. It got very personal between the two of them, and Hellinger actually had to apologize to Breen in a series of letters. So the big battle over “Brute Force” was trying to get it through the censor’s office, and it was Hellinger trying to make a realistic picture when Hollywood was still saddled with a production censorship code that had been written in the early 30s.

All movies mean different things to different people and one of the things that’s so much fun about film noir is that there’s endless speculation about the inner meaning or symbolism imbued by the director, writer or producer. I remember talking to Robert Wise about this stuff and he said, “I know people are very enthusiastic and I appreciate it but so much of the stuff that’s written about the symbolism in these pictures [isn’t true]. We just wanted to make a good picture, and it was based on either a short story, an article or a book.” Basically Wise and others have indicated that the symbolism that many people later attributed to their films really wasn’t there in the first place.

Certainly a lot of these directors had their individual styles. I won’t completely dismiss the auteur school, but most of them were storytellers. Yeah, there are certainly cases where people wrote characters that had some sort of meaningful symbolism or were taken from real events, but sometimes I think that speculation gets overblown and screenwriters often get overlooked in favor of directors. Making a movie is a collaborative effort, and I’m always hesitant to give credit to just one person, be it a producer or a director or an actor and say they were responsible for all of this because that’s not how it works.

The movie we’re going to show on August 14, “The Hunted,” was made for very little money. It was a “Poverty Row”-type of low-budget film, and yet it has some very redeeming value, mostly the screenplay written by the great Steve Fisher. The stories really had heft in a lot of these movies even though they were very low-budget. There are also some interesting players in that film, including Belita, an English ice skater.

HollywoodChicago.com: You recently recorded audio commentary with Kim Morgan on the DVD for another “Noir City: Chicago 3” selection, “New York Confidential.” The New York Anti-Crime Committee famously praised this film for its authenticity. How do you feel the film was reflective of its era?

Rode: When the Kefauver Senatorial Crime Committee started up in 1950, they took this roadshow and went to New York and Chicago and different cities, exposing what they called “the syndicate,” this shadow government that really did exist in certain cities like New York. You had Frank Costello really controlling the appointment of judges, and you had a key witness, Abe Reles, in a Murder Inc. investigation guarded by police. In 1941, Reles fell out of a window while being guarded by a phalanx of police. So certainly there was a lot of this going on, but Hollywood filmmakers seized on this and used it as a pretext to turn crime [stories] into “a lone guy or a district attorney or the government against the syndicate.” So you had a whole series of movies—“Chicago Confidential,” “New York Confidential,” “Kansas City Confidential,” “Captive City,” “The Big Combo,”—all of these movies with this syndicate organized crime motif where criminals were no longer leaders of a seven member gang with Edward G. Robinson or James Cagney blasting their way out. They were in a corporate environment, in a penthouse answering phones, sending minions out on hits and contracts.

Russell Rouse’s 1955 noir New York Confidential screens August 13 at the Music Box.

Photo credit: Kit Parker Films

“New York Confidential” was based on a novel but it was written in the 1940s before the Kefauver committee was formed. Certainly there is some realism in the film, but it is more of an entertainment mainly because of the cast. Broderick Crawford has the persona projection of a rogue elephant with a toothache. It also stars one of my favorite noir actors, Richard Conte. When I first showed this at the Egyptian Theatre in 2010, I invited Conte’s son, [Mark,] the very distinguished editor, and his wife. I don’t think anyone looked better in a Brioni suit than Richard. I asked [Mark], “Did your dad dress like that all the time?” and he said, “All the time.” I said, “So he wasn’t a guy who pushed a lawnmower with cutoffs on the weekend?” and he goes, “Absolutely not.” [laughs] Then you have Marilyn Maxwell, who was a real glamour queen and Bob Hope’s main squeeze on all those U.S.O. shows, and then a young Anne Bancroft, who left Hollywood because she was tired of playing Indians and acting in [B-movies like] “Gorilla at Large.” In fact, “New York Confidential” was a high water mark for her. She plays this beautiful but damaged daughter of the mob kingpin Broderick Crawford, and she ended up going back to New York, scoring on Broadway in “Two For a Seesaw” and “The Miracle Worker,” and went on from there to become one of our most respected actresses.

HollywoodChicago.com: Film historians have also claimed that another festival selection, “The Mob,” was a precursor to Elia Kazan’s vastly more well-known classic, “On the Waterfront.”

Rode: “The Mob” actually has very little in common with “On the Waterfront,” other than the backdrop of union corruption and gangsterism. “The Mob” is largely crime drama, part noir and part mystery. To me, the real star of “The Mob” is Bill Bowers, one of the best film noir screenwriters as far as pithy, funny, smartass dialogue. He also wrote one that people are really going to like called “Larceny,” with John Payne and Dan Duryea. If you haven’t seen that one, it’s really a lot of fun. The cast includes a young Shelley Winters.

HollywoodChicago.com: Have you ever wondered what “Sorry, Wrong Number” would’ve been like if it had starred Agnes Moorehead, who originated the role on radio, instead of Barbara Stanwyck?

Rode: Well I think Agnes Moorehead would’ve been great, and perhaps, in some ways, better than Stanwyck. But Moorehead was a supporting character actor and Stanwyck was a star. There’s no way Hal Wallis was going to have a film starring Burt Lancaster and Agnes Moorehead. That was never going to happen. I think Stanwyck’s good, and I think the film is actually very underrated and very suspenseful.

HollywoodChicago.com: Two key selections at this festival center on journalists: “Chicago Deadline” and “Deadline U.S.A.”

Rode: In “Chicago Deadline,” journalism is ancillary. “Deadline USA” captures the essence of a mid 20th century newsroom. I can’t think of another film that is more indicative of a part of our culture that is gone now. It is one of Bogart’s better overlooked pictures, it’s got a cast out of a character actor hall of fame and it has the vitality of [director] Richard Brooks. Everyone is going to watch that movie and go, “My god, what a terrific film.” It really does make you nostalgic for an era that has come to an end, back when people were reporters and really wrote stuff, not just pasted links on the Internet. Whether it’s film noir or not, I don’t know but I don’t care. [laughs] It’s a great movie.

HollywoodChicago.com: Was “Chicago Deadline” actually shot in the Windy City?

Rode: All the exteriors are filmed on location in Chicago. It is the only extant 35mm print of this movie that we know of and is being screened courtesy of the UCLA Film & Television Archive. It’s kind of like the newsprint version of “Laura,” where Alan Ladd becomes obsessed with Donna Reed. All of the films in this lineup are outstanding, so I encourage everyone to come out and see them. I’ll be talking and presenting opening weekend and then Foster Hirsch will come in on Monday and finish up the rest. I’m really looking forward to it.

| By MATT FAGERHOLM |