CHICAGO – In anticipation of the scariest week of the year, HollywoodChicago.com launches its 2024 Movie Gifts series, which will suggest DVDs and collections for holiday giving.

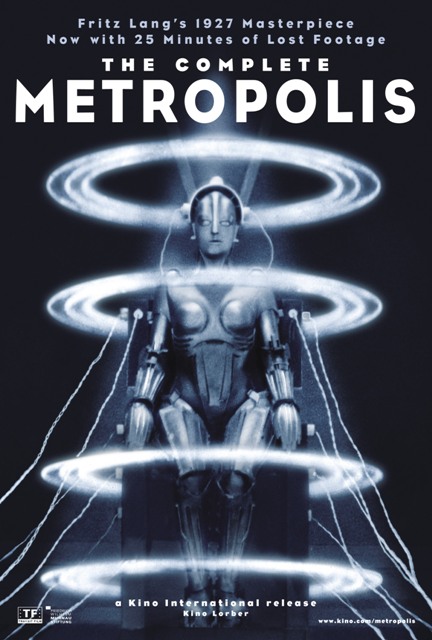

‘The Complete Metropolis’ a Must-See Movie Event

Rating: 5.0/5.0 |

CHICAGO – Not since the restoration of Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil” has a butchered cinematic classic been brought to such startling new life as “The Complete Metropolis.” Though Fritz Lang’s 1927 masterpiece “Metropolis” may never be restored to its original cut, this latest theatrical re-release is as close as film preservationists have ever gotten to recreating the legendary science-fiction epic in its entirety.

The twenty-five minutes of new footage added to this cut of “Metropolis” are nothing short of miraculous, especially in light of how they were found. Two summers ago, a 16mm back-up copy of the film’s original 35mm nitrate print was discovered in Buenos Aires. Though the print was badly damaged, it offered a wealth of missing scenes, as well as a complete blueprint for the film’s editing. Despite its permanently scratched surface, the Murnau Foundation decided to add the new material into the previously restored footage from the film’s 2002 restoration, resulting in a two-and-a-half hour cut of “Metropolis” that further illustrates the scope and power of Lang’s towering vision.

The Complete Metropolis

Photo credit: Courtesy of Kino International

But this picture is too marvelous to merely be considered homework for film historians. Few films have influenced the history of cinema quite like “Metropolis,” which creates an entirely new world not only from the ground up, but from below the ground as well. Part of Lang’s obsessive genius was his ability to externalize inner human struggle through the use of heightened abstract visuals, from the German Expressionism of his “Mabuse” pictures, to the American film noir of “The Big Heat.” In “Metropolis,” the conflict between blue-collar workers and the privileged bourgeoise is represented by the striking architecture of the titular setting. A sprawling modernist cityscape inhabited by the business-minded upper class sits atop a subterranean vision of hell known as “the Depths,” where zombie-like laborers live solely to work. The staggering detail and brilliant utilization of forced perspectives by photographer Eugene Shufftan, set designer Edgar G. Ulmer and art directors Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut, and Karl Vollbrecht, is best admired on the biggest screen possible.

Freder (wide-eyed Gustav Fröhlich), the son of Metropolis’s cold-hearted ruler Joh Frederson (Alfred Abel), is the film’s designated protagonist, though the most transfixing character is peace advocate Maria (the beguiling Brigitte Helm). She opens Freder’s eyes to the poverty existing within the Depths, which prompts him to question his father about the placement of these unfortunate citizens (Joh’s response: “It’s where they belong!”). Maria preaches about the need for a mediator to join together the hands (have-nots) and head (haves) of society, and her popularity amongst the workers threatens Joh, leading him to devise a scheme with the mad inventor Rotwang (Rudolph Klein-Rogge). They plan to create a mechanical being resembling Maria that will mislead the workers, though Rotwang (the local Caligari) has plans of his own. While the story includes some gaping plot holes, and may seem rather silly and melodramatic to contemporary audiences, its larger-than-life theatricality fits perfectly with Lang’s aesthetic, which infuses each frame with a nightmarish surrealism.

According to this restoration’s production notes, there are ninety-six individual segments added to this cut, many of which are additional reaction shots that significantly strengthen character depth and motivation. Sequences involving the machine’s bizarre dance, the worker’s riot, and the final chase are greatly expanded by an assortment of key shots. There’s also an entirely new subplot involving Fredersen’s leering henchman, The Thin Man, and his attempts to bribe the fired clerk Josaphat. Yet the single most dazzling addition highlights the spectacular invention of cinematographer Karl Freund, whose artful use of overlapping visuals is witnessed throughout the film. The scene involves a freed worker who’s lured from safety by the temptation of a night on the town. What follows is a delirious montage that’s guaranteed to excite even the most jaded movie buffs.

The Complete Metropolis

Photo credit: Courtesy of Kino International

If there is one minor flaw in this version of “Metropolis,” it is the recording of Gottfried Huppertz’s original score. There is nothing wrong with the music itself, which accompanies the visuals so impeccably that the film hardly ever feels “silent.” When Freder envisions the underground workers as slaves being devoured by the demonic face of a fiery god, Huppertz’s score packs an undeniable wallop. Yet the new recording is almost too successful at recreating the experience of a silent movie screening accompanied by live music. Apart from the orchestral score, the soundtrack includes clearly audible coughs, page turns, and in one unforgivable instance, muffled laughter. Imagine “The Imperial March” being interrupted by the sound of John Williams blowing his nose, and you’ll get the idea of how distracting these noises are to moviegoers yearning to fully envelop themselves in Lang’s universe.

Yet I’m still awarding this print of “Metropolis” the full five stars simply because it’s impossible to be anything but humbled and awe-struck while in its presence. If you love “Dr. Strangelove,” “Star Wars” or “Blade Runner,” then you cannot afford to miss seeing the picture that inspired them all. And since the film is so visually interpretive, the scratches on the new footage actually end up enhancing the experience. They give viewers the momentary sensation of falling downward…to the Depths!

| By MATT FAGERHOLM |