CHICAGO – In anticipation of the scariest week of the year, HollywoodChicago.com launches its 2024 Movie Gifts series, which will suggest DVDs and collections for holiday giving.

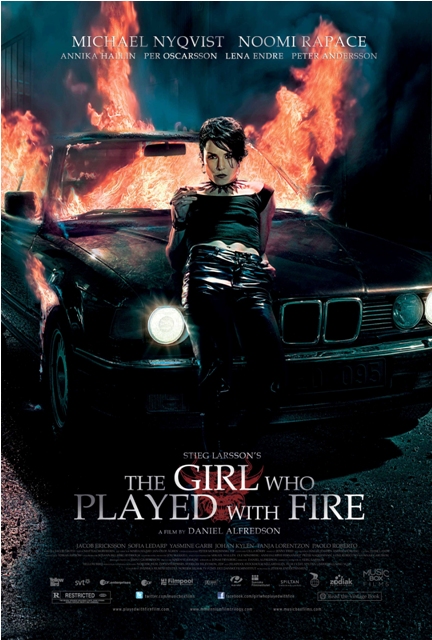

‘The Girl Who Played With Fire’ Snuffs Out Potential

Rating: 2.5/5.0 |

CHICAGO – Movie trilogies often are judged on the strength of their middle chapters. The “Star Wars” franchise wouldn’t have been continually embraced by new generations if “The Empire Strikes Back” hadn’t deepened the characters to such an extent that they became more than mere Jungian archetypes. If “Empire” jettisoned the franchise’s potential, “Attack of the Clones” brought it in for a crash landing.

“The Girl Who Played With Fire” is nowhere near the disaster of “Clones,” but considering the international appeal of its source material, the film is a definite letdown. It’s based on the second installment of Swedish author Stieg Larsson’s “Millennium Trilogy,” which was published posthumously, and gained tremendous popularity with readers worldwide. Larsson was also a journalist with strong antifascist beliefs, and worked at a small publication not unlike the one in his book series. His crime dramas follow an investigative journalist, Mikael Blomkvist, and an antisocial computer hacker, Lisbeth Salander, as they piece together various mysteries, some of which reside in themselves.

The Girl Who Played With Fire

Photo credit: Music Box Films

When Blomkvist and Salander teamed up in “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo,” the film version caught fire, largely because of the mesmerizing lead performances from Michael Nyqvist and Noomi Rapace (impeccably cast as Lisbeth). One of the built-in weaknesses with the follow-up is the fact that Nyqvist and Rapace are never allowed to share the screen, since their characters only communicate via e-mail. Without their chemistry to drive the film’s narrative momentum, the story collapses into a series of half-connected crises and exposition-laden plot twists. There’s always something happening onscreen, but the two main protagonists often remain stagnant, and so does the film’s momentum. “Fire” feels like a considerably longer film than “Tattoo,” even though it’s over twenty minutes shorter than its predecessor.

While the first installment centered on a labyrinthine mystery involving a wealthy family with a history of Nazism, “Fire” turns its focus inward on the ominous backstory of Lisbeth, whose deep-seated hatred of abusive men was spawned from a profoundly troubled childhood. A year has passed since she first joined forces with Mikael, and the two allies are brought into each other’s orbit when Lisbeth is wrongly convicted of a triple homicide. Mikael is determined to prove her innocence, and sets out on another whodunit caper, though his role here is conspicuously shortened in favor of an ever-expanding ensemble. There are so many new names and faces that audiences may feel motivated to take notes, or better yet, sketch a map.

The Girl Who Played With Fire

Photo credit: Music Box Films

The ultimate problem with this page-to-screen adaptation is the same one that irreparably marred “The Da Vinci Code”—there’s simply too much plot. Literature works on the mind in an entirely different way than cinema does. Readers are allowed much more time to digest a plot and linger over its complexities, thus causing plot twists to truly jolt the mind. Cinema also has the power to jolt and surprise, but not when it has to constantly keep explaining itself. “Fire” consists of nothing but plot twists, and none of them pack a real punch, mostly because the audience never gets the chance to catch up. There are few things less engaging than the SparkNotes version of a crime thriller. Who wants to rush through plot developments as if they were a series of bullet points? Director Daniel Alfredson sorely lacks the sense of pacing and atmosphere that Niels Arden Oplev brought to “Tattoo.” His workmanlike approach to the material causes the audience to feel even more distanced from the elusive characters.

Stripped down to its bare elements onscreen, Larsson’s books often feel like a male fantasy of female empowerment. Despite his homely appearance, Mikael seems capable of bedding any woman within his reach, even a bisexual badass like Lisbeth. Her crusade against “men who hate women” is passionately supported by Larsson, though his graphic sequences of abuse are all the more repellant when depicted on film, and occasionally cause the movies to skate dangerously on the edge of exploitation. Other aspects of the story become rather silly when simplified, a fact that is glaring apparent in the final act of “Fire,” which includes several stunningly implausible elements, including a death-defying escape that defies all laws of common sense, a cartoonish villain worthy of James Bond, and a plot twist straight out of (dare I say it?) “The Empire Strikes Back.”

Though “The Girl Who Played With Fire” hasn’t entirely destroyed my faith in the film series, it hasn’t gotten me perched on the edge of my seat in anticipation for the final installment, “The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets’ Nest.” All of these pictures would clearly fit better in an elongated televised miniseries. Though Rapace’s fierce work still warrants a viewing, consider this “Girl” a misfire.

| By MATT FAGERHOLM |