CHICAGO – In anticipation of the scariest week of the year, HollywoodChicago.com launches its 2024 Movie Gifts series, which will suggest DVDs and collections for holiday giving.

Film Feature: The 10 Best Overlooked Films of 2011

CHICAGO – Some films never get a fair shot with audiences. They open in a handful of art house theaters scattered throughout the country before inconspicuously landing on DVD. Passionate movie lovers are left with the task of championing these unjustly obscure titles and helping them to acquire the audience they deserve.

Before I reveal my picks for the top ten Best Overlooked Films of 2011, here are the ten runners-up:

“Autoerotic”

Autoerotic

While Steve McQueen’s magnificent art film, “Shame,” plunges into the dark depths of sexual addiction, Joe Swanberg and Adam Wingard’s “Autoerotic” takes a decidedly more playful approach to similar material. Though Swanberg has made a series of uncommonly intimate films about the sex lives of twentysomething Chicagoans, he’s never attempted a film as overtly comic as this one, and Wingard proves to be an ideal collaborator. “Autoerotic” is easily Swanberg’s most accessible film to date, and will hopefully introduce more viewers to one of Chicago’s most gifted and prolific filmmakers. The 72-minute film consists of four somewhat interconnected short subjects about couples who find unusual ways to deal with ordinary problems. One man goes to extreme lengths to make himself more well-endowed. Another makes an outlandish request of his ex that proves he’s more interested in genitalia than whatever is connected to it. The most memorable vignette features Frank V. Ross and Kris Swanberg, who seem to be reprising their roles from Swanberg’s excellent web series, “Young American Bodies.” As is usual of Swanberg’s honest and unflinching work, the sex scenes are explicit but never exploitative, while revealing a surprising amount of insight into modern relationships.

“Buck”

Buck

There’s a striking early moment in Cindy Meehl’s documentary where horse trainer Buck Brannaman slows the speed of his walking to demonstrate how he might move as an old man. His horse observes this change and adjusts its movement accordingly by following its owner at a slower speed. It becomes quickly apparent that Brannaman has somehow created a silent language with horses that allows him to calm and navigate their minds. As one of the nation’s most respected practitioners of the “natural horsemanship” method, Brannaman spends the majority of his time on the road, holding clinics at various locations throughout the continent where he’s gradually built a base of avid participants. Meehl’s film becomes an extension of Brannaman just as his horses become an extension of him. It’s a stripped-down and straightforward portrait with a great deal of depth and wisdom that applies to life beyond the stable. The structure he imposes on the horses is mirrored by the structure provided by his own rigid schedule, which may function as a form of protection. Brannaman’s need for order in his life seems to have sprung directly from his troubled upbringing. At a time when America’s divisive culture is anchored by shouting matches with the power to drown out all common sense, I suspect every person could benefit from emulating Brannaman’s serene, no-nonsense approach to dealing with conflict.

“Circumstance”

Circumstance

Filmmaker Maryam Keshavarz’s elegantly lensed, viscerally effective feature debut made headlines earlier this month when its producer, Karin Chien, criticized the Producers Guild of America for deeming it a “foreign language film,” despite the fact that it was financed in the U.S. It’s the latest ill-conceived effort to categorize films by their dominant language as opposed to their country of origin. “Circumstance” is clearly the work of an Iranian American attempting to portray the repression of her native country from a clear-eyed perspective. This is a passionately observed tale of star-crossed lovers that delivers a real erotic charge. Beguiling newcomers Nikohl Boosheri and Sarah Kazemy star as two teenagers who keep their shared attraction a secret while dreaming of life in a more enlightened land. Reza Sixo Safai plays Boosheri’s older brother, a troubled man still living on his parent’s allowance, who starts clinging to fanaticism and sexual obsession in order to construct an “adult” life for himself. Safai’s actions in the film are reprehensible, but he is suffering under the same repression. Since the characters can’t display their passion in public, it’s externalized through deftly executed fantasy sequences. Keshavarz’s extreme close-ups of lips and fingers create more sexual tension than any amount of nude scenes ever could. She is a filmmaker to watch.

“Cold Weather”

Cold Weather

This is the sort of film that Video On Demand was made for. It doesn’t require a big screen or surround sound to fully envelop the audience into its story. Director Aaron Katz’s longtime collaborators, cinematographer Andrew Reed and composer Keegan DeWitt, impeccably set the mood and tone for an overcast Oregon-set noir from the very first frame. The effortlessly natural Cris Lankenau (star of Katz’s “Quiet City”) plays Doug, a young slacker who initially fits the profile of many a mumblecore protagonist: single, unemployed, and seemingly aimless. During the film’s first 40 minutes, it appears that “Weather” will be yet another brooding, blue-tinted relationship drama from the Sundance labs. But Katz stealthily builds tension throughout the first act until the picture emerges as a low key yet no less infectious variation on Woody Allen’s underrated 1993 farce, “Manhattan Murder Mystery.” Devoid of distracting punchlines, Katz’s film is ultimately more gripping and leads to a genuinely tense climax. By viewing the plot purely through the limited gaze of its innocent protagonists, the film succeeds in making the viewer feel like a participant in the unfolding story rather than a detached observer. Reed’s elegant imagery brings a haunting intrigue to the most mundane spaces. This may be the most visually poetic American indie since Bradley Rust Gray’s “The Exploding Girl.”

“Jane Eyre”

Jane Eyre

Ever since she materialized on the first season of HBO’s masterful series, “In Treatment,” Mia Wasikowska has quickly emerged as one of the most magnetic actresses of her generation. She’s blessed with the sort of face that’s impossible to look away from. And in Cary Fukunaga’s sublime adaptation of Charlotte Brontë’s gothic melodrama, Wasikowska proves to be a hypnotic beauty. Fans of Fukunaga’s galvanizing debut film, “Sin Nombre” may initially regard “Eyre” as a giant departure, yet both films are not without their similarities: ravishing photography, impeccable production design and a story anchored in the arduous coming-of-age journey of a strong female protagonist. Amelia Clarkson is also a standout as the young Jane who grows up to be a governess for the formidable Mr. Rochester, played by the tirelessly versatile Michael Fassbender. Rochester’s hopeless infatuation with Jane leads to a series of complications, and the 12-year age difference between Fassbender and Wasikowska make their romantic entanglements more than a little unsettling. Yet it’s a testament to both actors’ skills that their romance registers as touching rather than creepy. Brontë’s novel has received an endless array of screen adaptations, but few have felt as authentic and heartfelt as Fukunaga’s overlooked gem.

“Like Crazy”

Like Crazy

“Please, please tell me what they looked like,/Did they seem afraid of you?/They were kids that I once knew…/They were kids that I once knew…” And so go the lyrics of the Stars song, “Dead Hearts,” that poignantly plays over the end titles of Drake Doremus’s remarkable romance. It won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival, as well as snagged an award for its radiant leading lady, Felicity Jones, but didn’t receive the attention it deserved during its limited theatrical release. What makes the picture such a stand-out is its structure. As the helmer of indie gems “Spooner” and “Douchebag,” Doremus has a background in crafting intricately layered character studies on a tight budget. While so many studio films leave their most interesting moments on the cutting room floor in order to advance the narrative, this film plays like an assortment of deleted scenes. The script, co-authored by Doremus and Ben York Jones, is more interested in exploring key nuances than hitting expected plot points. Scene after scene depicts the push and pull of a long distance relationship struggling to stay alive against all odds. There are times when British college student Anna (Jones) and Jacob (Anton Yelchin) feel the need to move on but are entirely unable to let their connection die. Both stars deliver their best work to date, while cinematographer John Guleserian proves to have a masterful eye for detail. Though the film clocks in at a brisk 90 minutes, it overflows with moments of painful recognition for anyone who’s ever been haunted by a relationship that was—for one reason or another—unsustainable.

“Margaret”

Margaret

With a running time clocking in around two and a half hours, this barely released curiosity from Fox Searchlight still plays like a work in progress. Tonally conflicting scenes careen into one another as if large chunks of the narrative had been plucked out altogether. A longer cut edited by Martin Scorsese and approved by the film’s director Kenneth Lonergan (“You Can Count On Me”) has yet to be screened, but what remains in the theatrical version is far more interesting than countless completed pictures. It’s a fascinating mess that actually works in spite of itself, with a messy structure that mirrors the turbulent inner life of its central heroine, played in a breathtaking performance by Anna Paquin (prior to “True Blood”). Her performance embodies female adolescence stripped of all clichés. There isn’t a trace of romanticism in the scene where Margaret (Paquin) loses her virginity to a casual acquaintance. Her angry altercations with her workaholic mother, stage actress Joan (J. Smith Cameron), resonate on an entirely authentic level. And when a friendly yet careless exchange with a bus driver causes him to fatally strike a pedestrian, Margaret reacts in a way any blindsided teenager would. She initially reports that the accident was no one’s fault, but nagging guilt causes her to seek justice. Her compulsive need to bring about an ideal ending to this tragedy conflicts with the mundane contradictions of the real world. Yet this straightforward premise doesn’t even begin to convey the audacity and complexities of this picture. Lonergan may be biting off more here than he can possibly chew, but even with its running time slashed, this film is alive in a way that few films are. John Cassavetes would’ve loved it.

“Norman”

Norman

Like Jonathan Levine’s unlikely feel-good comedy, “50/50,” this terrific indie dramedy may prove to be a great source of catharsis and comfort to people suffering through the daily trials brought on by disease. For audiences merely seeking a fine evening of entertainment, both films also fit the bill. From the moment the titular teenage protagonist rips open the shuddering door of his locker and shoots a morose glance at its contents, Norman (Dan Byrd) has the viewer thoroughly absorbed in his moment-to-moment experiences. As he observes his father, Doug (Richard Jenkins), gradually succumb to stomach cancer, the audience shares Norman’s mounting anxiety about the sudden crises that could befall him at any moment. Life at home is a ticking time bomb, while school is a melancholy dirge. With his father’s illness a mystery to his peers, Norman suddenly claims that he has stomach cancer and has little time left to live. This comes as startling news to the student body, particularly Emily (Emily VanCamp), the girl who instantly won Norman’s heart with her kindness, charm and love of Monty Python. The romantic subplot is tenderly observed, but the real heart of the picture lies in the scenes between Norman and Doug. The toll of functioning as the sole caregiver can easily make one feel as if they are going through the physical turmoil themselves, and that is ultimately what “Norman” is about. The fact that it manages to be as hilarious as it is moving is a remarkable achievement.

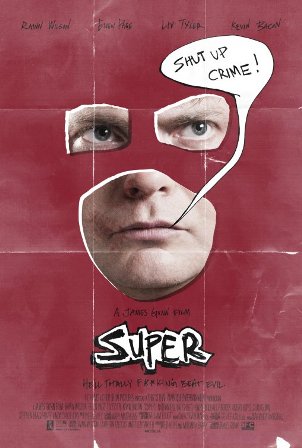

“Super”

Super

A great oddball howl of rage delivered with deadpan zeal by writer/director James Gunn. Yes, this jet-black satire about a vigilante superhero draws obvious comparisons to Matthew Vaughn’s rollicking guilty pleasure, “Kick Ass,” but Gunn’s film is far darker and a hell of a lot more fun. Rainn Wilson further perfects his “disgruntled loser” persona as Frank D’Arbo, a genial yet witless man who transforms into a vengeful monster after his wife (Liv Tyler) falls for a drug dealer (Kevin Bacon, displaying the pompous glee of a schoolyard bully). Fed up with all the evil in the world, Frank creates a homemade costume and transforms into the Crimson Bolt. Yet since he lacks any semblance of superpowers, Frank relies instead on his ability to whack evildoers in the head with a wrench. As his sidekick and muse Libby (nicknamed “Boltie”), Ellen Page gives one of year’s great comic performances. Libby is so exhilarated by the newfound adventure that her energy reaches frightening levels of hysteria. Unlike the hyper-stylized blood-spurts in “Kick Ass,” the violence in “Super” is graphic and genuinely disturbing, thus making it impossible for viewers to dismiss the fractured human drama beneath the onscreen chaos. It’s a kick to the cojones that hurts so good.

“Win Win”

Win Win

One of the finest unsung performances of the year was delivered by Paul Giamatti in Tom McCarthy’s microcosm of the financially strapped Midwest. Giamatti has become one of those actors whose work is so consistently brilliant that he’s routinely taken for granted. His portrayal of a professional back-stabber in George Clooney’s “The Ides of March” was also Oscar-worthy, but quickly became lost in the holiday shuffle. Mike Flaherty, the lawyer that Giamatti plays in “Win Win,” is an equally nefarious but considerably more sympathetic character. After double-crossing one of his clients in order to better provide for his family, Flaherty becomes deeply conflicted when faced with the client’s young grandson, Kyle (wonderfully played by real-life champion wrestler Alex Shaffer). Mike takes Kyle under his wing and gets him involved in the wrestling team that he’s volunteered to coach. Yet the dirty truth of Mike’s dirty double dealings threatens to reach the surface once Kyle’s mother (Melanie Lynsky) re-enters the picture. There are no heroes and villains in “Win Win,” and certainly no winners and losers—only an assemblage of flawed yet endearing people attempting to navigate their way through the murky waters and obstacles of everyday life.